My love and admiration for Maya Angelou really is no secret or accident. The women in my family loved Angelou more than any other writer. Her books were essential reading, second only to the Bible. They were regularly missing from their book-shelved position and psalmic in everyone’s reading voice. My grandmother, a woman who prefers to be told the stories than to read them, kept a number of dog-eared Angelou poetry collections in her home, as well as in the shed that we would frequently visit and clean out during our summer holidays. Whenever she happened across one of the books, she’d pause the cleaning and ask me to pick a poem and read it to her. My mother cited Angelou’s poetry often. Like most of her books, they felt like collectibles; secrets belonging only to this household. Unlike her other ‘too-grown-for-you’ books, she’d leave them at a reachable height on the bookshelf.

It was no surprise when it came to choosing my dissertation title that, having purchased my own version of ‘I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings’, I had decided on an Angelou-centred thesis. I wanted to end three years of my Russell Group education focusing intently on the words of a Black woman who felt as good as home.

Recently, I’ve been returning to some of the writers who wrote about themselves that I discovered during my English degree. I’m reading Patti Smith’s essays after falling in love with her memoir and the artful introduction she gave me to the genre. I’m also reading Audre Lorde, again, forever, just like 6/7 years ago. I take ‘Your Silence Will Not Protect You’ with me on errands in the city and it stays with me while stuck in the rush hour that could have become my life, had I chosen it instead of this for myself. I’ve returned to writing about Angelou too, though not just her writing. In fact, less of her writing, which as I write from my mother’s home, I can see right here from where I sit.

Amani Hope, from Read Like Mad, prompted a question in notes about the books that changed our lives. I found myself pushing the entire autobiographical series, of course, and noticed how much of Angelou’s words still live in me. Six years after graduating, my thesis about ‘Voicelessness and Black Women’s Autobiography’ has come to hold up a mirror, gently, as I continue my non-academic writing life. I move myself around the world and talk and write and assert who it is that I am and why. It’s a very scary but very unavoidable part of who I’ve become, as writer, as essayist, as nomadic traveler constantly introducing myself, always leaving and offering and receiving goodbyes. There is literally no space for voicelessness in my life.

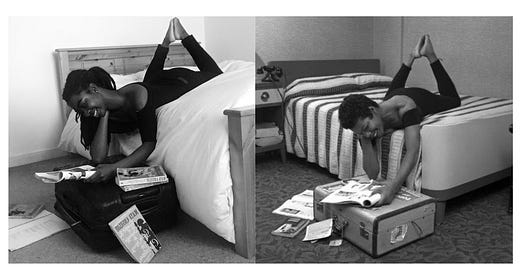

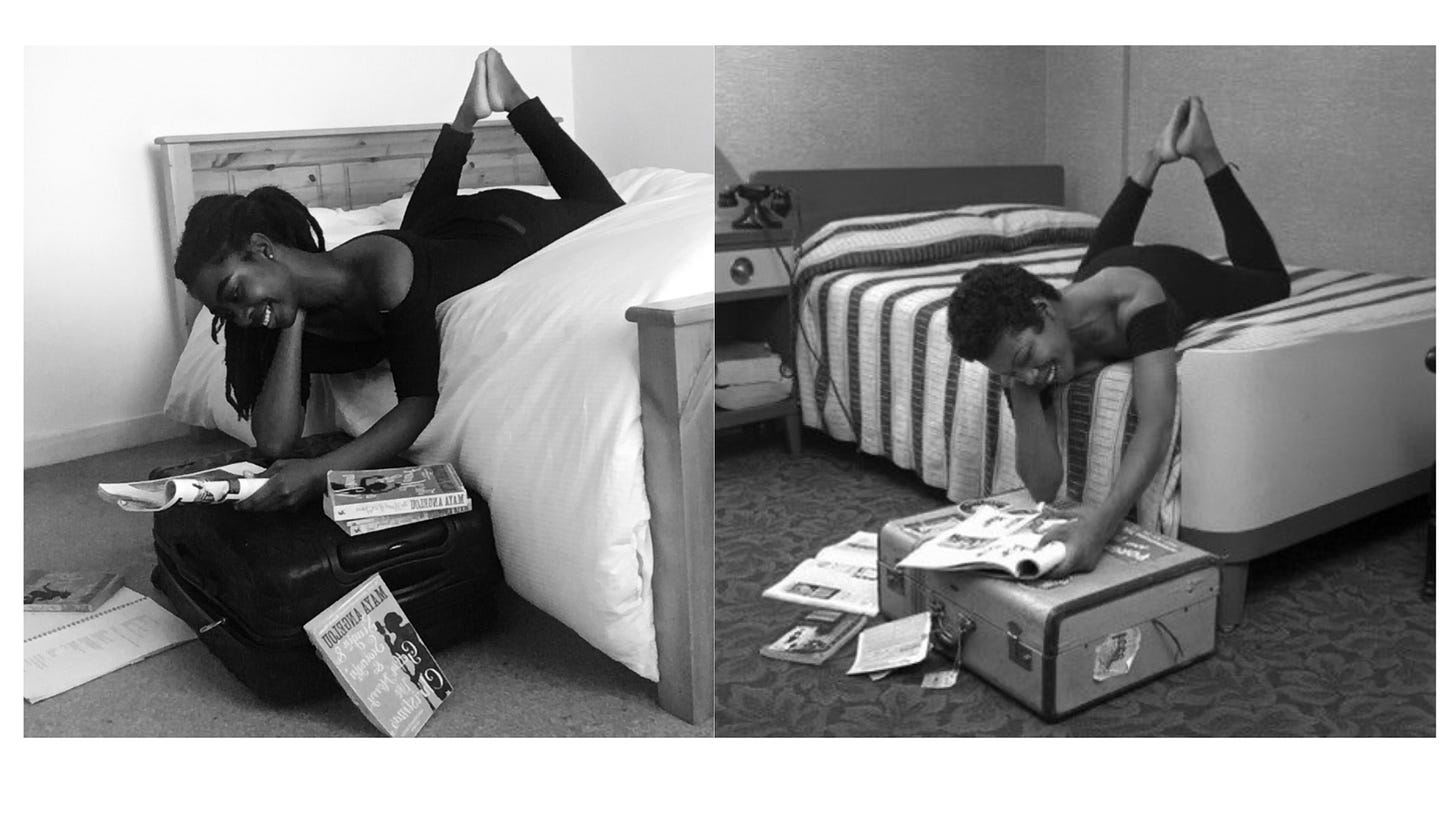

I did this photoshoot during one of the early lockdowns of 2020. It was one of those many wholesome moments of being inside with myself, playing around with my inner child's desire to create without rush. On this day, I used a stack of books in place of a tripod and took this portrait of myself as a recreation of one of my favourites. I set up my shot, trying my best to capture Angelou’s environment, her carefree, uncontainable essence, and her love for wordy literature. After reading and analysing the entire autobiographical series, I felt a closeness to Angelou and her commitment to never dismissing nor becoming a caged bird once more.

Angelou, a woman who spent a period of her life completely mute, became a voice of a generation and gave permission to Black women, writers and otherwise, and those who wished to be unforgiving in their truth, size, and mannerisms, to be indulgent in their voice. This alone emboldened me in those days of being inside, seeing and hearing myself.

The photograph of Angelou, taken by G. Marshall Wilson, was just before a Calypso performance at the Village Vanguard in New York City. Angelou’s voicefulness, if you will, extended beyond her writing. I imagined her as her favorite star girl. And why wouldn’t she be? She was tall and vibrant and quite hard to ignore and shameless by choice and force, she was an Aries - oh what else - a woman and mother too, and she seemed, from what I understood at the time of my studies, to be very magnetic.

And I am too, now. Since I’m not afraid of the risk of travelling to somewhere where I have no friends or have never been, I see the potential for magic — if only I pronounce it with my own voice. I’ve taken from Angelou, a lesson in writing and becoming: the need to break the silence, louder each time and with each journey.

Travelling solo as a Black woman is about regrouping in silence, in order to hear yourself again, and trusting your new, returning voice. It’s the fine line between being seen and remaining invisible enough to remain safe; to slip between the growing crowd, mistaken as being of the land in some places. To be seen as friend not tourist. To be respected in ways that have been taken from you. To be understood and welcomed in several languages.

It’s also to be able to state who you are away from the history of who you’ve always been. I think of Angelou traveling around Europe during her time touring with Porgy and Bess, speaking to whoever she could with the help of a pocket dictionary of whichever language was necessary. Or, the way that the emotional weight of being on, or flying over, African soil left her speechless, and yet full of language emotionally. There is something so magical in trusting the world with what you have to say. And trusting yourself to keep doing it over and over again.

Stoooop the recreation of this photograph is so sweet!!! ❣️

There’s a lot to unpack here but first I want to say thank you for sharing. Secondly, that photo you recreated is GORG. When you spoke about 2020 being a time where you could explore your inner-child really touched me, I experienced sometimes similar that I often wish to go back to. I’m struggling to get back there.

Thank you again for sharing, thank you for being you. Thank you to your family for having such an admiration for Maya Angelou, it is reflected in your writing and for that I am grateful.